Phoresy is a temporary interaction and usually interspecific relationship wherein a phoretic animal, known as a phoront, attaches itself to a host animal to facilitate dispersal (Seeman & Walter, 2023). The term “phoresy” is rooted in the Greek word “phorein,” signifying ‘to carry.’ The phoront is an organism that lacks significant independent locomotion ability over long distances. Therefore, it relies on the assistance of a highly mobile host for effective and extended dispersal.

Phoresy is commonly observed in the arthropod world (Clausen, 1976; Huigens & Fatouros, 2013; Veiga, 2016). Mites, in particular, are p extensively documented as frequent participants in phoretic associations (Veiga, 2016). I have encountered numerous instances where phoretic mites attach themselves to the bodies of various arthropods from Sri Lanka (Fig. 1). All these sightings were recorded in two villages: Minuwangete (7.71° N, 80.24° E) in the Northwestern Province and Thirappane (8.18° N, 80.50° E in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka.

Phoretic interactions may be mutualistic, commensal, parasitic, or parasitoid relationships (Seeman & Walter, 2023). This article primarily focuses on the parasitoid relationships that involve phoresy within a specialized group of parasitoid wasps. It is particularly interesting to explore, as certain egg parasitoids have evolved to use phoresy strategically, effectively overcoming spatial and temporal discontinuities between the mating and ovipositing locations of their hosts.

Phoresy among parasitoids is primarily observed in some egg parasitoids (Clausen, 1976; Fatouros & Huigens, 2012). Phoretic relationships in egg parasitoids are commonly observed within the hymenopteran family Scelionidae, as well as in select species of Trichogrammatidae, Eulophidae, and Encyrtidae (Fatouros & Huigens, 2012). Phoretic scelionid egg parasitoids are predominantly reported on orthopteran and heteropteran hosts, with a lesser occurrence on lepidopterans (Veenakumari et al. 2012). Insect eggs, being inconspicuous, pose a challenge for egg parasitoids, which heavily depend on indirect cues emitted by adult hosts to locate and access the eggs (Colazza et al., 2010). Moreover, there’s a general assumption that egg parasitoids lack the capability for extensive directed flight over long distances (Suverkropp et al. 2009). Therefore, some egg parasitoids overcome this problem through this kind of strategy, the phoresy.

I documented some leaf-footed bug species, Anoplocnemis cf. phasianus (Fabricius, 1781), with accompanying scelionid egg parasitoids on their bodies in two villages in Sri Lanka: Thirappane and Minuwangete (Fig. 2). In both instances, the scelionid egg parasitoids were attached to males of leaf-footed bugs. It is likely that during the mating process of the male bug, the wasp transfers onto the female, subsequently remaining on the female’s body until she lays her eggs. These parasitoid wasps were specifically located on the hind femora and the head area, positioned between the compound eyes. These areas likely serve as safe environment, minimizing disruptions that could be caused by the hosts. Moreover, these parasitoids did not employ mandibles to attach themselves to the host’s body.

Another observation of phoresy observed on a mating couple of Cletus sp. (Coreidae) from Minuwangete (Fig. 3). The scelionid wasp was attached on the dorsal face of the head in between compound eyes of the female Cletus.

Another interesting observation was made in the vicinity of my home in Minuwangete. Another the tiny wasp tightly attached to the abdominal plates of adult gaudy grasshopper species, Orthacris sp. by its’ mandibles (Fig. 4). In contrast to other parasitoids discussed in this article, this particular species uses mandibles to attach itself to the adult host while keeping its legs in resting position. This specific scelionid species is a striking resemblance to a species documented from the South Indian states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu known as Sceliocerdo viatrix (Brues, 1917). Originally, this parasitoid species was described as being attached to the abdomen of the Deccan grasshopper (Colemania sphenarioides Bolívar, 1910) (Brues, 1917). However, Veenakumari et al. (2012) documented another host, Neorthacris acuticeps (Bolívar, 1902), a species taxonomically close to the Sri Lankan Orthacris genus, which I have recorded hosting this parasitoid. It is plausible that this parasitoid is either the same Sceliocerdo viatrix (Brues, 1917) or a closely related new species. According to Veenakumari et al. (2012), Sceliocerdo is a monotypic genus, endemic to India. However, this article suggests a potential geographical extension of the genus beyond India, prompting the need for additional taxonomic investigations to confirm this expansion.

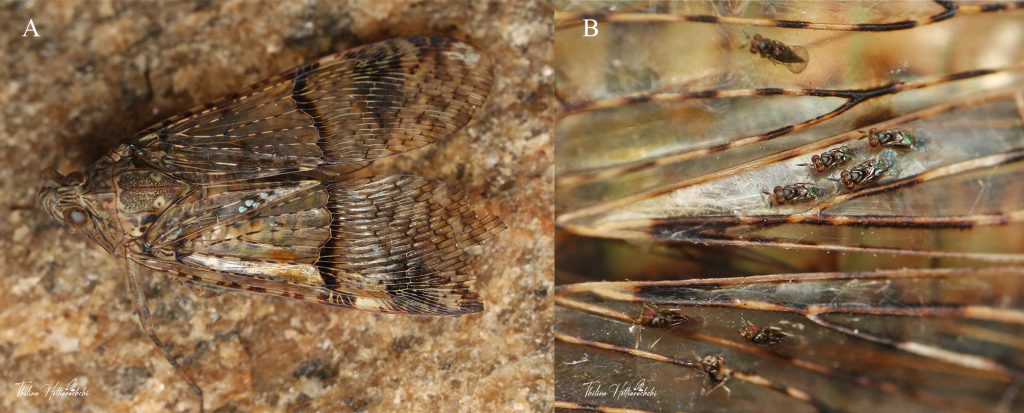

I encountered a lanternfly species (Fig. 5A) resting on a cave roof in the Thirappane area. This particular species was later determined to belong to the genus Dichoptera. During the image processing, I was intrigued to discover very small wasps attached to its wings (Fig. 5B). I counted eight parasitoid wasps on its wings. Based on wing and antennae characteristics, these wasps appear to belong to the family Eulophidae. Phoresy has been observed in only a few species within this family, with some instances documented in the genus Emersonella (Cuignet et al., 2007). But these species are recorded as egg parasitoids of tortoise beetles.

Phoresis has been documented in Podagrion spp. (Torymidae), where females attach themselves to the wings or other parts of their adult mantid hosts (Bordage 1913, Xambeu 1881). Notably, these specific parasitoids specialize in parasitizing mantid eggs. It’s truly fascinating how Podagrion sp. adeptly address the challenge of locating oothecae by seeking out gravid female mantids and patiently awaiting their host to lay eggs (Figs 6A&B). This female mantid (Odontomantis cf. planiceps Haan, 1842) is near to laying her egg case. After few weeks later I found this ootheca (Fig. 6) in the same vicinity I found that gravid mantid and the shape of the ootheca also pretty match with the usual shape of Odontomantis cf. planiceps ootheca. So possibly this belongs to that female. Interestingly I found very freshly emerged this Podagrion sp. on the ootheca (Figs. 6C&D).

In conclusion, the enchanting world of arthropods unveils a wealth of extraordinary findings, especially in countries like Sri Lanka, where the tropical climate amplifies biodiversity. This article sheds light on specific areas that warrant in-depth research, aiming to unravel the mysteries of this captivating world and raise awareness among the general public. This, in turn, plays a pivotal role in conservation efforts, contributing to the protection and preservation of these astonishing creatures—insects!

Acknowledgements

Thank to Dr. Jason Gibbs for helping me in enhancing this article through editing and providing me valuable comments. Additionally, my appreciation extends to everyone who aided in identifying certain species through the photographs I uploaded to the iNaturalist website.

References

Bordage, E. 1913. Nôtes biologiques recueillies à l’Ile de la Reunion. Bulletin scientifique de la France et de la Belgique, 46: 377–412.

Brues, C.T. 1917. Adult hymenopterous parasites attached to the body of their host. —Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 3: 136-140.

Clausen, C. P. 1976. Phoresy Among Entomophagous Insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 21(1), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.21.010176.002015

Cuignet, M., Hance, T. and Windsor, D. 2021. Phylogenetic relationships of egg parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) and correlated life history characteristics of their Neotropical Cassidinae hosts (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 42 (3), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.09.005

Fatouros, N. E. and Huigens, M. E. 2012. Phoresy in the field: natural occurrence of Trichogramma egg parasitoids on butterflies and moths. BioControl, 57(4), 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-011-9427-x

Huigens, M. E. and Fatouros, N. E. 2013. A Hitch‐Hiker’s Guide to Parasitism: The Chemical Ecology of Phoretic Insect Parasitoids. In Chemical Ecology of Insect Parasitoids (pp. 86–111). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118409589.ch5

Seeman, O. D. and Walter, D. E. 2023. Phoresy and Mites: More Than Just a Free Ride. Annual Review of Entomology, 68(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120220-013329

Veenakumari K., Rajmohana K. and Prashanth, M. 2012. Studies on Phoretic Scelioninae (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) from India along with description of a new species of Mantibaria Kirby. Linzer biologische Beiträge, 44: 1715–1725.

Veiga, J. P. 2016. Commensalism, Amensalism, and Synnecrosis. In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology (pp. 322–328). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800049-6.00189-X

Xambeu, M. V. 1881. Hyménoptère parasite de la Mantis religiosa. Annales de la Société entomologique de France, 6: 113–114.